Early Schools of the Garland Area

The history of Garland schools begins in the late 1840s, soon after Texas gained statehood and settlers began to migrate into the area. Probably the first school in what is now Garland was a one-room log building erected on his property by early settler Abner Keen. The Keen family included besides Abner, his wife Susan, several of their school-age children and also the young families of two married sons, John and William Keen. Abner, John, and William Keen had come in 1846 from Indiana to lay claim to 640-acre Peters Colony headrights on Duck Creek.

The school built by Abner Keen for the education of his children and those of his sons was constructed on the west side of the creek near a flowing spring presumably very near Abner’s home cabin. The exact date of its construction is not known, but it is specifically identified in an 1849 entry in the district records of the Methodist church. The existence of this one-room log school is repeatedly mentioned in histories of Garland, but its origin as the Abner Keen school as early as 1849 has only recently been elucidated.

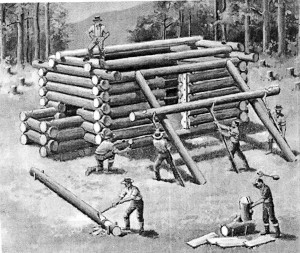

The form of this little log school is well documented. It was windowless, since glass window panes and milled wood window frames were not available on the frontier. A door at the north side of the room and another at the south provided ventilation and light when weather permitted. In winter a field stone fireplace with a stick and mud chimney gave both heat and light. The floor and benches were made of split logs, called puncheons, smoothed on one side. Since no nails were to be had, all joints were held together by notching, wooden pegs, or rawhide strips. The cracks in the walls between the logs were filled (“chinked”) with mud. The roof was constructed of shakes split off logs and weighted in place by cross pieces. These same techniques were used in building the log cabins and barns of the settlers.

The form of this little log school is well documented. It was windowless, since glass window panes and milled wood window frames were not available on the frontier. A door at the north side of the room and another at the south provided ventilation and light when weather permitted. In winter a field stone fireplace with a stick and mud chimney gave both heat and light. The floor and benches were made of split logs, called puncheons, smoothed on one side. Since no nails were to be had, all joints were held together by notching, wooden pegs, or rawhide strips. The cracks in the walls between the logs were filled (“chinked”) with mud. The roof was constructed of shakes split off logs and weighted in place by cross pieces. These same techniques were used in building the log cabins and barns of the settlers.

The Keen schoolhouse was also used for religious gatherings by all local denominations, but particularly by the Methodists, since the Keens were of that persuasion, several actually being Methodist preachers. A grandson of Abner, Newton A. Keen, recalled as a boy attending a “great protracted meeting” held there. A “protracted meeting” usually lasted several days and attracted people from far and wide. [One questions how a “great” gathering of any kind could have been held in that tiny one-room cabin, but things do seem bigger when one is a kid.] According to Newt’s recollection a puncheon “mourners’ bench” extended through the center of the room from front door to back. Congregants seeking an inner experience of God’s saving grace knelt at this bench, men on one side and women on the other, while others sang, shouted and “pounded” on them, reminding them of the eternal damnation awaiting them if they did not find and accept God’s means to salvation.

Abner sold the north half of his headright, containing the Duck Creek school, to George W. Routh in 1856. Routh in turn donated the acre on which the school stood to Dallas county School District No. 12. It is said that soon afterward a new and more accommodating structure was erected to replace the original log cabin school. The new building was a single 18’ x 24’ room of frame construction, the milled material most likely having been hauled by ox wagon from Shreveport. It had a south-facing door and a window on east and west sides but it lacked a ceiling. It was heated by a wood-burning stove. This and the earlier log school are believed to have stood on the wedge of land now bounded roughly by South Garland Avenue, Edgebrook Drive, and the creek.

The early years of the Duck Creek school were difficult ones. At first there was no public funding and the sparseness of population made it difficult to raise adequate subscription funds to pay the teacher. By the mid-1850s Dallas County had established school districts but provided them with only minimal assistance. The only books were the assortment the students were able to dig up here and there, many having brought books from their former homes in other states. It was nothing unusual for as many as three pupils to share one book. Patrons of the school boarded the teacher in their homes to supplement the small amount they were able to pay in salary. The students were usually excited to have their teacher stay in their home.

The Duck Creek schoolhouse, besides its educational and religious functions, in its earliest days also served as a justice-of-peace courtroom, a meeting place for the local Grange and debate society, and as a polling place. It has been reported that at the beginning of the Civil War local men gathered there to drill prior to departing for Confederate service.

After the Civil War the increase in the local population prompted an effort to upgrade the school program and facilities. Under the leadership of teacher F. J. Abernathy the room was ceiled, two long study tables added and the crude puncheon benches replaced with benches with backs. The teacher was even provided a desk with drawers for his papers. Somewhat later upper division classes were added and the name of the school changed to Duck Creek Academy, but because of inadequate facilities the program was soon abandoned.

Early School Life

The boys fetched drinking water for the school in a bucket from the nearby spring. There was only one dipper, from which everyone drank. Students brought their lunches in syrup buckets with tight fitting lids. Those who lived a long distance from school rode horses, which were hitched to trees or to hitching racks. The saddles were laid in one corner of the school room. The older boys chopped firewood and the girls swept the floor.

There was, of course, no such thing as playground equipment, so the school children entertained themselves with what nature provided along the creek. At that time there was dense woodland along both sides of the creek. They snacked on berries, wild grapes, and haws and chewed “stretch berries” as a substitute for chewing gum. The boys rode saplings and swung on a grapevine swing. For a long time there was no bridge across Duck Creek near the school, so wading in the creek was a favorite diversion in warm weather and was often a necessity for students coming from the east side of the creek. When Duck Creek was up even crossing on horseback could be too risky, so eventually a suspension foot bridge was built across the creek. It is reported that some of the older boys took great pleasure in swaying the bridge as girls tried to cross over it.

Student progress in those days was not measured by advancement in grade levels (i.e., first grade, second grade, etc.), but rather was expressed as what reader the student was “in” (the McGuffy readers ranged in difficulty levels from first to sixth). Friday afternoons brought a welcome diversion from the classroom routine for the students at the Duck Creek school. On those days the students competed with each other in recitation of poetry, debating, or spelling matches administered from Webster’s blue-back speller. The school year concluded with “closing exercises,” designed to impress parents with how much their children had progressed that year. These “exercises” consisted of speeches, expressive readings, poetry recitations, songs, and instrumental performance by the students, and were popular social events for the entire community.

Other early local schools

Contemporary with the Duck Creek school in the early 1870s, and possibly even earlier, was a log school located about one mile northeast across the creek near the present intersection of the Katy and Santa Fe railroad tracks and a short distance northeast of the Historic Square. Presumably it was established for students who lived on the east side of Duck Creek, since crossing the creek to reach the Duck Creek school was often hazardous for children before the suspension footbridge was built.

Another pioneer school was held in the old Locust Grove community in what is now extreme southeast Garland as early as 1860. It was taught by James Carmack and was held in vacant residences since no school building had been built there at that time.

Acknowledgment: Most of the historical information used in this article originated in the memoirs of Kate Jones James and of Newton Asbury Keen, both of whom attended the Duck Creek school.

Social